This was a problem in SECCON 2024 qualifiers (which I played with PPP) which I solved with the help of my debugging/reversing tool, Pyda. This writeup serves as both a writeup of the challenge, and a showcase of the capabilities of Pyda.

Getting started

First up is getting the challenge running. You can use a ubuntu:24.04 Docker container to run the challenge,

but since we want to run under Pyda I opted to copy the libraries from there into the pyda image:

FROM ubuntu:24.04 as target

FROM ghcr.io/ndrewh/pyda

COPY --from=target /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ /target_libs/

RUN apt install -y patchelf

COPY F /F

RUN patchelf --set-interpreter /target_libs/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 --set-rpath /target_libs/ /F

RUN apt install -y binutils

We can run the challenge and we see it’s a flagchecker.

root@6792c69f4f0d:/opt/pyda# /F

FLAG:

OK – time to play a game i like to call “how far can we get without opening binja”:

First, we use the compare-logging example Pyda script to print out the operands to all of the comparison instructions in the program:

root@6792c69f4f0d:/opt/pyda# pyda examples/cmplog.py -- /F

cmp_locs: 46

FLAG: AAAAAAAAAA

cmp @ 0x15787 rdx=0x100000003 rax=0x100000001 False

[...]

cmp @ 0x15787 rdx=0x100000002 rax=0x100000001 False

cmp @ 0x18276 rbx=0x0 rax=0x0 True

cmp @ 0x182a7 rcx=0xa rdx=0x40 False

"Wrong"

We see the final comparison before “Wrong” is printed is between 0xa (the number of As we entered) and 0x40.

This tells us that the flag is probably 64 bytes long.

Once we use the correct flag length, there is a larger number of comparisons, which ultimately ends in this suspicious comparison:

cmp @ 0x1891b rcx=0xc3df45f3 rdx=0x11793013 False

Changing the input changes the value in rcx, but not rdx – which suggests that the goal

is to make these values match at the end of the flag transformation.

We can use Pyda’s backtrace feature to print out a (demangled!) backtrace at this comparison:

p = process(io=True)

e = ELF(p.exe_path)

e.address = p.maps[p.exe_path].base

p.hook(e.address + 0x1891b, lambda p: print(p.backtrace_cpp(short=True)))

# Run the process until FLAG: is received

p.recvuntil("FLAG: ")

p.sendline(("ABCDEFGH").ljust(0x40, "A")) # ABCDEFGHAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA.....A

# Run the process until termination

p.run()

In this script, we passed io=True to the Pyda process() call and used the pwntools-style p.recvuntil and p.sendline

interface to send our input directly.

root@6792c69f4f0d:/opt/pyda# pyda script.py -- /F

[F+0x1891b] auto std::operator!=<unsigned int, std::__cxx11::b...onst&, std::integral_constant<unsigned long, 0ul>)

[F+0x1b9c8] void std::__invoke_impl<void, std::operator!=<unsi...st&, std::integral_constant<unsigned long, 0ul>&&)

[F+0x1a6ac] std::__invoke_result<std::operator!=<unsigned int,...st&, std::integral_constant<unsigned long, 0ul>&&)

[F+0x189b5] std::__detail::__variant::__gen_vtable_impl<std::_...allocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > const&)

[F+0x18dd3] decltype(auto) std::__do_visit<std::__detail::__va...allocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > const&)

[F+0x18ea2] void std::__detail::__variant::__raw_idx_visit<std...allocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > const&)

[F+0x16755] bool std::operator!=<unsigned int, std::__cxx11::b...allocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > const&)

[F+0x3b0c] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...:allocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> >) const

[F+0xc9cb] main::{lambda(auto:1, std::variant<unsigned int, s...r<Cons> >) const::{lambda()#2}::operator()() const

[F+0x14617] std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cxx11::basic_str... >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> >) const::{lambda()#2}&)

[F+0x13208] std::enable_if<is_invocable_r_v<std::variant<unsig... >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> >) const::{lambda()#2}&)

[F+0x105fa] std::_Function_handler<std::variant<unsigned int, ...t::{lambda()#2}>::_M_invoke(std::_Any_data const&)

[F+0x167d4] std::function<std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...>, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>::operator()() const

[F+0x3ba6] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[F+0xcc75] std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cxx11::basic_str...:allocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> >) const

[F+0x53fe] decltype(auto) fix<main::{lambda(auto:1, std::vari...locator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> >&) const &

[F+0x5539] main::{lambda()#1}::operator()() const

[F+0x13347] std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cxx11::basic_str...a()#1}&>(std::__invoke_other, main::{lambda()#1}&)

[F+0x10753] std::enable_if<is_invocable_r_v<std::variant<unsig...Cons> >, main::{lambda()#1}&>(main::{lambda()#1}&)

[F+0xe3d3] std::_Function_handler<std::variant<unsigned int, ...n::{lambda()#1}>::_M_invoke(std::_Any_data const&)

[F+0x167d4] std::function<std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...>, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>::operator()() const

[F+0x3b91] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[F+0x67b4] main

[libc.so.6+0x2a1ca] __libc_init_first

[libc.so.6+0x2a28b] __libc_start_main

[F+0x3325] _start

The backtrace (even the full version) is pretty awful and seems to be filled with a bunch of anonymous lambdas. It’s looking like we might actually have to open binja :(.

shared_ptr<Cons> stood out to me though, so the first thing we’ll do is print out the arguments on every call to that constructor.

Printing out the lists + the 1st transformation

We can add this short bit of code to our Pyda script to print out the lists as they are constructed:

def cons(p):

print(f"cons {hex(u32(p.read(p.regs.rsi, 4)))}")

p.hook(e.address + 0x15a06, cons)

First, it prints a bunch of constants (ending with the constant we saw in the comparison earlier).

cons 0xb7e9a2a4

cons 0x1904c652

cons 0xbe8afe4d

cons 0xbd18775a

cons 0x82841cf4

cons 0xd2c1d5af

cons 0xf389c4a

cons 0x451f151a

cons 0xd5689a8c

cons 0x927b5bd9

cons 0xf86c82d7

cons 0x34bc7c60

cons 0x97aef869

cons 0x2c0cccdd

cons 0x88d2ec9b

cons 0x11793013

And then a bunch more (smaller) constants

cons 0x7

cons 0x0

cons 0xc

cons 0xd

cons 0x2

cons 0xf

cons 0xb

cons 0x8

cons 0x6

cons 0x5

cons 0x9

cons 0x4

cons 0xa

cons 0x1

cons 0xe

cons 0x3

Followed by what is clearly our input (in reverse order and grouped into 4-byte chunks)

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x41414141

cons 0x48474645

cons 0x44434241

and the result of some transformation!

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x4e4e4e4e

cons 0x48464549

cons 0x444a414e

I figured this transformation out relatively quickly with just some guesswork:

# Take the numbers from the first list (in reverse)

>>> m = [7, 0, 12, 13, 2, 15, 11, 8, 6, 5, 9, 4, 10, 1, 14, 3][::-1]

# Now map 0x41 => 0x4e, one nibble at a time

>>> hex(m[0x4])

'0x4'

>>> hex(m[0x1])

'0xe'

2nd transformation

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0xd36975c1

cons 0xe14de95e

The next transformation (e.g. from 0x4e4e4e4e => 0x93af4e5e) was somewhat more perplexing. I checked if it could be a constant XOR, but that didn’t work. It seems like we might actually have to open binja (we have to use a rev tool to solve a rev challenge???).

I looked through the backtraces for the first two transformations (filtering for only functions in the main:: namespace).

For the first transformation:

cons 4e4e4e4e

[F+0x3bfe] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...:allocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> >) const

[F+0x8741] main::{lambda(auto:1, std::variant<unsigned int, s...r<Cons> >) const::{lambda()#2}::operator()() const

[F+0x3ba6] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[F+0x86d0] main::{lambda(auto:1, std::variant<unsigned int, s...r<Cons> >) const::{lambda()#2}::operator()() const

[F+0x3ba6] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[...]

For the second transformation:

cons 5e4eaf93

[F+0x3bfe] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...:allocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> >) const

[F+0x8e67] main::{lambda(auto:1, std::variant<unsigned int, s...r<Cons> >) const::{lambda()#2}::operator()() const

[F+0x3ba6] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[F+0x8dcc] main::{lambda(auto:1, std::variant<unsigned int, s...r<Cons> >) const::{lambda()#2}::operator()() const

[F+0x3ba6] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[...]

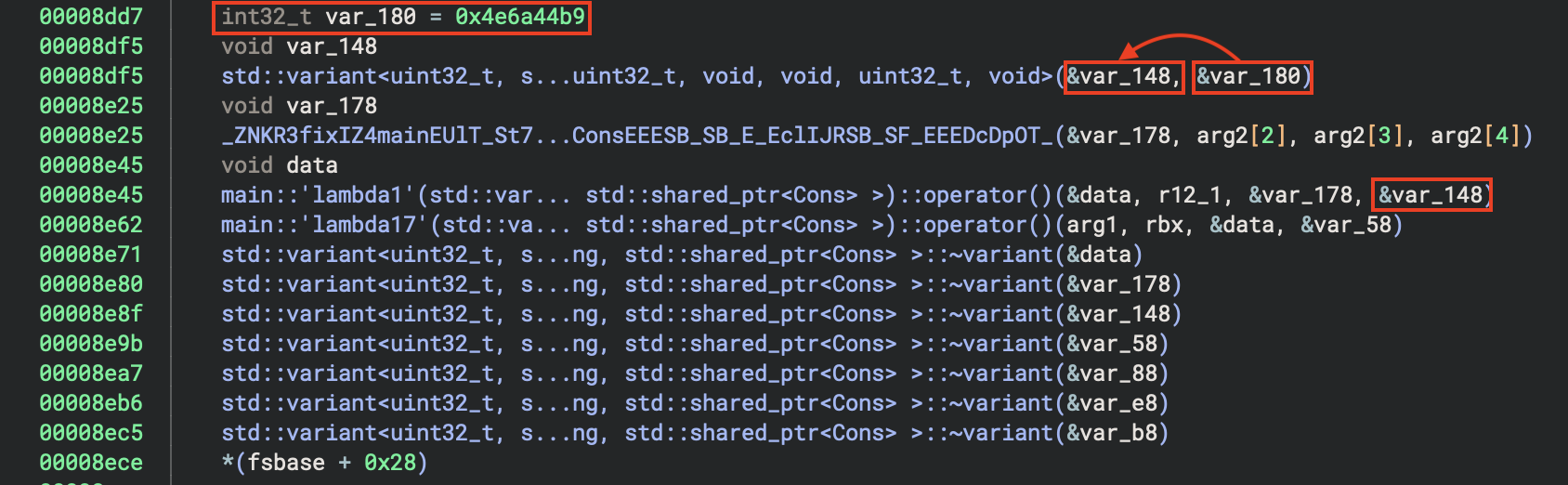

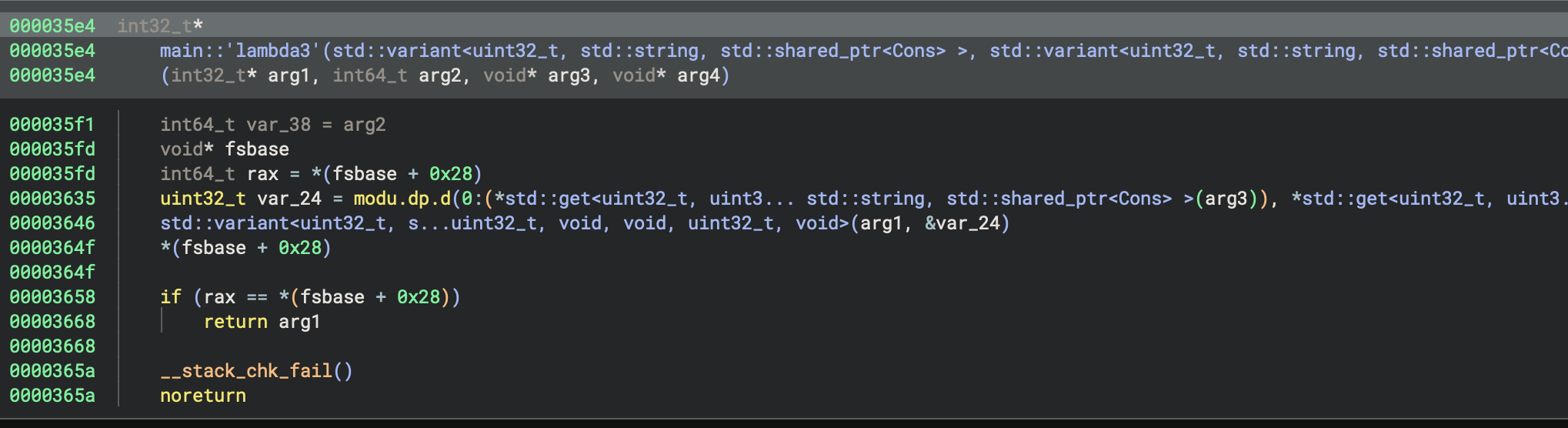

It seems that F+0x3bfe is an operation common to both transformations; looking at the caller F+0x8e67

in the second transformation we find a function with a suspicious-looking constant:

So the transformation here is not XOR, it’s multiplication (mod 2^32)!

>>> hex((0x4e4e4e4e * 0x4e6a44b9) & 0xffffffff)

'0x93af4e5e'

3rd transformation

The backtrace for the next transformation is also different:

[F+0x3bfe] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...:allocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> >) const

[F+0x983e] main::{lambda(auto:1, std::variant<unsigned int, s...erator()() const::{lambda()#2}::operator()() const

[F+0x3ba6] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[F+0x9f2e] main::{lambda(auto:1, std::variant<unsigned int, s...r<Cons> >) const::{lambda()#2}::operator()() const

[F+0x3ba6] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[F+0x97bc] main::{lambda(auto:1, std::variant<unsigned int, s...erator()() const::{lambda()#2}::operator()() const

[F+0x3ba6] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[F+0x9f2e] main::{lambda(auto:1, std::variant<unsigned int, s...r<Cons> >) const::{lambda()#2}::operator()() const

[F+0x3ba6] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[F+0x97bc] main::{lambda(auto:1, std::variant<unsigned int, s...erator()() const::{lambda()#2}::operator()() const

[F+0x3ba6] main::{lambda(std::variant<unsigned int, std::__cx...ocator<char> >, std::shared_ptr<Cons> > ()>) const

[...]

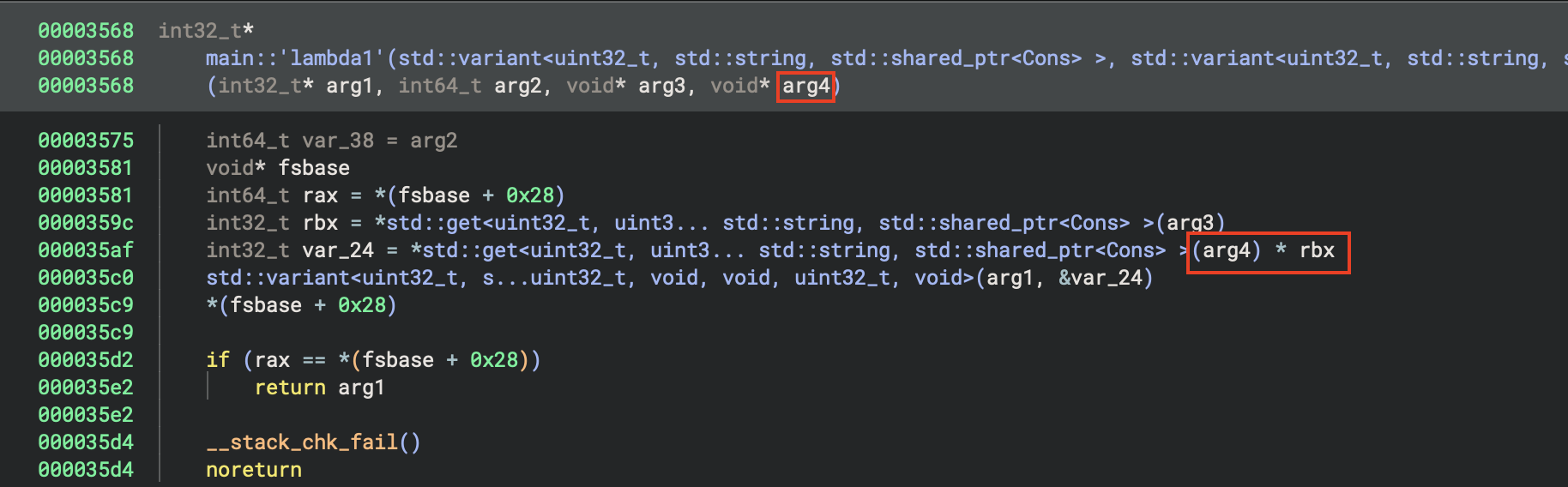

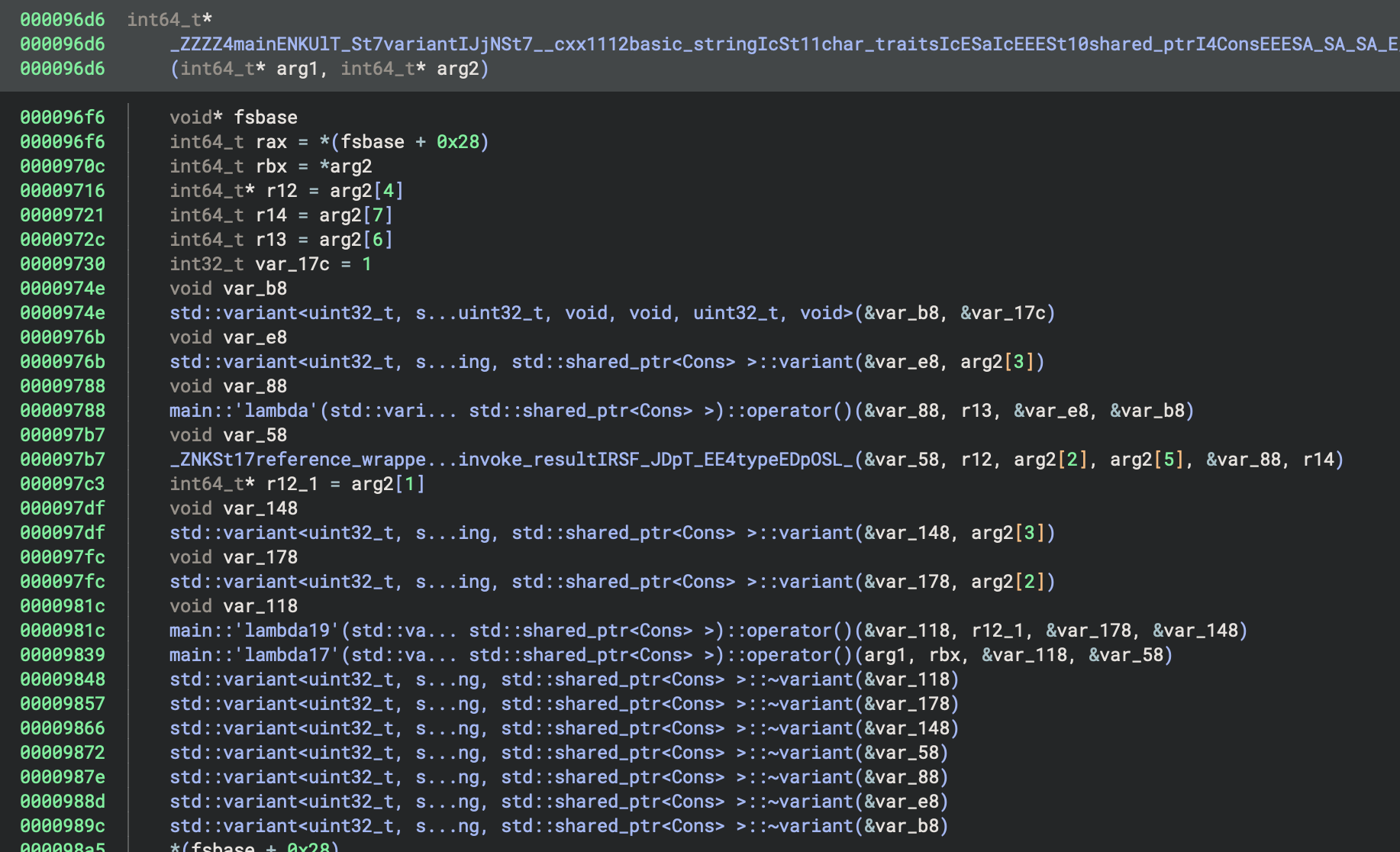

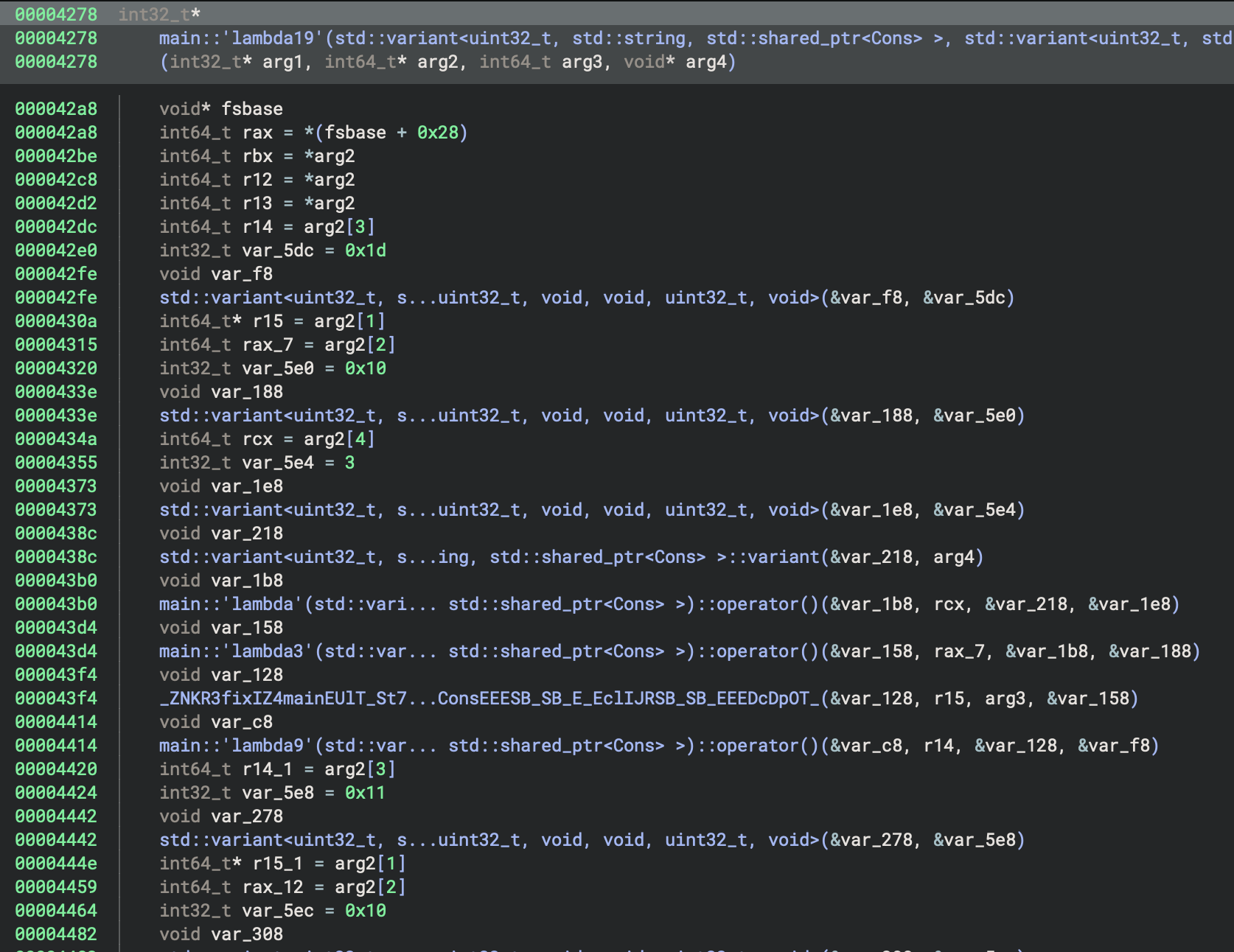

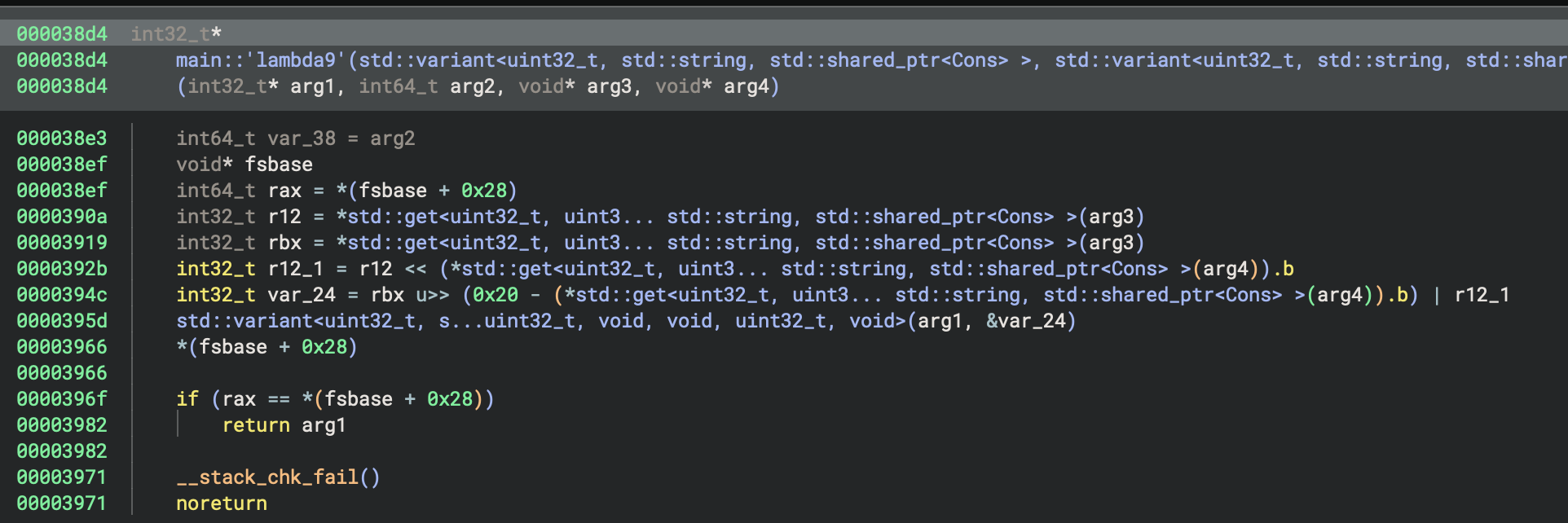

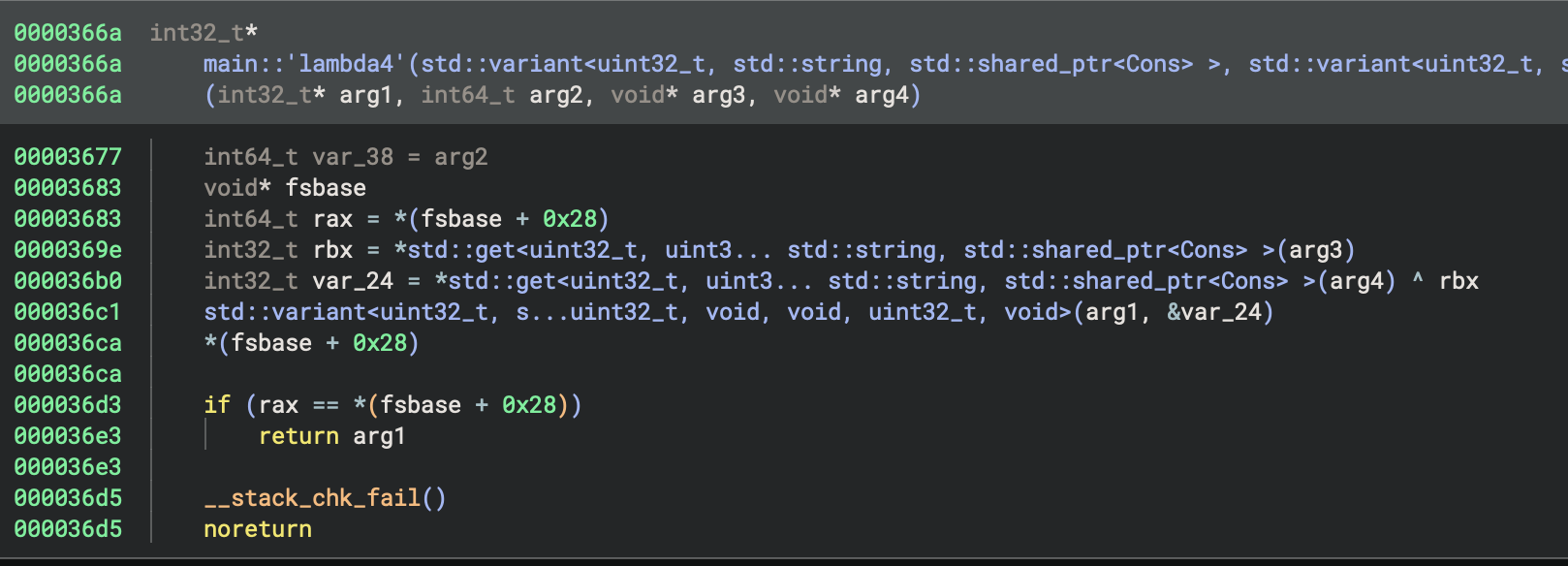

At F+0x983e we find a similar pattern to the second transformation with a call to lambda17 preceded by a

call to another function, lambda19.

The transformation looks complicated, but is made up of calls to several sub-functions:

The first performs a mod operation, the second performs a left-rotate, and the third performs an XOR. It’s a bit unclear what the operands are here, so I used Pyda to log the values used in the mod and XOR:

p.hook(e.address + 0x000035e4, lambda p: print(f"mod {p.read(p.regs.arg3, 16).hex()} {p.read(p.regs.arg4, 16).hex()} "))

p.hook(e.address + 0x000036ae, lambda p: print(f"xor {hex(p.regs.rax)} {hex(p.regs.rbx)}"))

Looking at the cons operations resulting from this transformation (which are, as with all of the transformations, constructed in reverse-order so the bytes from the beginning of the input

are processed last), we find that the last three integers are left un-modified from the previous transformation.

Then we see several calls to the mod and xor functions

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

cons 0x93af4e5e

mod 0f000000fd7f0000e982c45dc17f0000 10000000fd7f0000b0533be4fd7f0000

mod 0e000000c17f0000e0473be4fd7f0000 10000000fd7f0000e0473be4fd7f0000

xor 0xd275e9cb 0x9cbd275e

mod 0d000000fd7f000020463be4fd7f0000 10000000fd7f0000d685c45dc17f0000

xor 0x4ec8ce95 0xd7a72f49

mod 0c000000fd7f0000d0443be4fd7f0000 10000000fd7f0000d0443be4fd7f0000

xor 0x996fe1dc 0x93af4e5e

cons 0xac0af82

mod 0e000000fd7f0000e982c45dc17f0000 10000000fd7f0000d0613be4fd7f0000

mod 0d000000c17f000000563be4fd7f0000 10000000fd7f000000563be4fd7f0000

xor 0xd275e9cb 0x9cbd275e

mod 0c000000fd7f000040543be4fd7f0000 10000000fd7f0000d685c45dc17f0000

xor 0x4ec8ce95 0xd7a72f49

mod 0b000000fd7f0000f0523be4fd7f0000 10000000fd7f0000f0523be4fd7f0000

xor 0x996fe1dc 0x93af4e5e

cons 0xac0af82

[...]

Using the rotation constants (29, 17, and 7) from the decompiled lambda19:

>>> hex(rol(0x93af4e5e, 29))

'0xd275e9cb'

>>> hex(rol(0x93af4e5e, 17))

'0x9cbd275e'

>>> hex(rol(0x93af4e5e, 7))

'0xd7a72f49'

So we can guess (based on the fact that the small numbers are mod 16) that these correspond to indices in the list – and the complete transformation for the new list element at index 12 (note indices 13-15 were appended to the list above unmodified) must look like:

k1 = rol(inp[15%16], 29)

k2 = rol(inp[14%16], 17)

k3 = rol(inp[13%16], 7)

k4 = inp[12%16]

res = k1 ^ k2 ^ k3 ^ k4

and at the end appears to finish with indices 0-3.

mod 03000000fd7f0000e982c45dc17f0000 10000000fd7f000030fd3be4fd7f0000

mod 02000000c17f000060f13be4fd7f0000 10000000fd7f000060f13be4fd7f0000

xor 0xd275e9cb 0x9cbd275e

mod 01000000fd7f0000a0ef3be4fd7f0000 10000000fd7f0000d685c45dc17f0000

xor 0x4ec8ce95 0xb4bae0e9

mod 00000000fd7f000050ee3be4fd7f0000 10000000fd7f000050ee3be4fd7f0000

xor 0xfa722e7c 0xe14de95e

cons 0x1b3fc722

Putting it all together

Looking at the subsequent transformations, we find that it’s just these three transformations, repeated 8 times.

We’ll use Z3:

from z3 import *

inp = [BitVec('inp%d' % i, 8) for i in range(0x40)]

s = Solver()

for i in range(0x40):

s.add(inp[i] >= 0x20)

s.add(inp[i] <= 0x7e)

For the first transformation, I just constructed a if-then-else tree for each possible nibble (since trying to encode the map lookups in SMT can be kindof annoying).

def step1_map(inp):

m = [7, 0, 12, 13, 2, 15, 11, 8, 6, 5, 9, 4, 10, 1, 14, 3][::-1]

m = [BitVecVal(x, 4) for x in m]

mapped_inp = []

for i in range(0x40):

# Create an if-then-else tree

low_nibble = inp[i] & 0xf

high_nibble = LShR(inp[i], 4)

new_low = m[0]

for j in range(1, 16):

new_low = If(low_nibble == j, m[j], new_low)

new_high = m[0]

for j in range(1, 16):

new_high = If(high_nibble == j, m[j], new_high)

mapped_inp.append(Concat(new_high, new_low))

return mapped_inp

For the second transformation we can use this nice one-liner:

def step2_xor(inp_ints):

return [x * BitVecVal(0x4e6a44b9, 32) for x in inp_ints]

The first two transformations are straightforward to re-apply, but there’s some weird edge conditions in the third transformation

(as the indices used change each time the transformation is used). Because I was printing out everything that was appended to the list

and every call to the mod operation, getting the pattern right was not super difficult, but I ended up writing two versions of the

transformation with slightly different edge conditions.

def step3_rotate(inp5, skip):

inp6 = []

for i in range(min(skip, 3)):

inp6.append(inp5[i])

for i in range(skip, skip+13):

k1 = rol(inp5[(i+3)%16], 29)

k2 = rol(inp5[(i+2)%16], 17)

k3 = rol(inp5[(i+1)%16], 7)

k4 = inp5[(i+0)%16]

inp6.append(k1 ^ k2 ^ k3 ^ k4)

for i in range(16-(3-min(skip, 3)), 16):

inp6.append(inp5[i])

assert len(inp6) == 16

return inp6

inp3 = step3_rotate(inp2, 0)

# ...

inp6 = step3_rotate(inp5, 1)

# ...

inp9 = step3_rotate(inp8, 2)

# ...

inp12 = step3_rotate(inp11, 3)

def step3_rotate2(inp5, index):

inp6 = []

for i in range(0, 16):

if (i >= index and i < index+3):

inp6.append(inp5[i])

else:

k1 = rol(inp5[(i+3)%16], 29)

k2 = rol(inp5[(i+2)%16], 17)

k3 = rol(inp5[(i+1)%16], 7)

k4 = inp5[(i+0)%16]

inp6.append(k1 ^ k2 ^ k3 ^ k4)

assert len(inp6) == 16

return inp6

inp15 = step3_rotate2(inp14, 1)

# ...

inp18 = step3_rotate2(inp17, 2)

# ...

inp21 = step3_rotate2(inp20, 3)

# ...

inp24 = step3_rotate2(inp23, 4)

Final solve script is here

Why should you use Pyda?

Most of what I did in this write-up could have been accomplished with a (reasonably simple?) GDB script. I would argue that Pyda APIs are generally more ergonomic and the resulting scripts are shorter than with GDB scripting (or with other instrumentation-based tools such as Frida).

Pyda supports many of the same capabilities you might have otherwise expected from a debugger: for example,

you can redirect execution (i.e., by simply updating p.regs.rip) and intercept syscalls.

But unlike traditional debuggers, Pyda provides faster instrumentation for multithreaded programs (i.e., without

forcing all threads to stop for every breakpoint), and allows you to easily interleave execution (e.g., with p.run_until(pc) or pwntools-style p.recvuntil(b"string"))

with I/O (e.g., with pwntools-style APIs like p.sendline(b"...")).

You can check Pyda out here.